Alaska IEA Goals

Alaska’s Integrated Ecosystem Assessment program facilitates the delivery of assessments, provides ecosystem science to management, relevant stakeholders, and community members in the Alaska region to support effective Ecosystem-Based Management. They are carried out as a collaboration with the Alaska Fisheries Science Center(AFSC,) and the OAR Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory (PMEL), community and university partners, and regional management councils to integrate field research, data, and models to inform management decisions.

How the Alaska IEA team uses the IEA framework to support Ecosystem-Based Management

The Alaska Integrated Ecosystem Assessment (IEA) team works in close partnership with established programs for ecosystem monitoring, analysis and assessment programs at AFSC and PMEL, collectively implementing all stages of the IEA approach to Ecosystem-Based Management (EBM) in Alaska’s marine ecosystems. The Alaska IEA team focuses on the “final steps” of delivering ecosystem science conducted in Alaska to management bodies, in particular the North Pacific Fisheries Management Council and the NOAA Fisheries Alaska Region, and ensuring the delivery of results in relevant, stakeholder-informed, and actionable management advice.

Specific steps include:

- Defining goals through the completion of Fisheries Ecosystem Plans (FEPs) for Alaskan ecosystems, to establish open and transparent processes for meeting ecosystem goals and objectives within the context of current Fisheries Management Plans (FMPs)

- Defining the system through the delivery of conceptual models of Alaskan coupled socio-ecological systems linking human needs to marine ecosystems, for use in stakeholder scoping

- Assessing the ecosystem through the extension and improvement of Ecosystem Status Reports (ESRs) for Alaskan ecosystems, including the development of “early-warning” indicators and procedures for establishing action thresholds for making precautionary EBFM decisions within existing FMPs

- Assess risk and evaluate management strategies through the development and delivery of an “end-to-end” suite of modeling tools for the eastern Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska large marine ecosystems; this modeling suite provides indicators of past conditions, seasonal forecasts, and long-term forecasts that allow for extensive, stakeholder-driven explorations of management strategies and risk assessment; To learn more about the modeling suite go here

- Provide science to management through the delivery of statistical tools for multi-species and ecosystem fisheries models to make these tools “management-ready” for annual tactical advice to fisheries managers

Alaska Ecosystems

Alaska’s shoreline is 44,000 miles long, more than double the length of the East and West coasts combined, providing a diversity of habitats for marine life and supporting important ecosystem services for Alaska’s communities and economy. Marine ecosystems in Alaska are dynamic and subject to the influence of human-induced changes from climate change, fishing, shipping, and extraction of oil and gas activities. The Alaska region is made up of 5 distinct ecosystems: the Gulf of Alaska (GOA), the Aleutian Islands (AI), the Eastern Bering Sea (EBS), the Beaufort Sea, and the Chukchi Sea (Alaskan Arctic). These support extensive high-value commercial fisheries, indigenous community’s subsistence uses, oil and gas development, and many other economic and cultural uses. Each of these regions is distinct in ecosystem structure and function and human activity.

Science to support vibrant marine ecosystems and coastal communities

Alaska’s marine ecosystems and coastal communities have co-evolved over millennia and across a wide range of habitats that span the fjord systems of Southeast Alaska with dramatic steep basins and rapid freshwater input, the highly complex and diverse shorelines of the numerous islands of the Aleutian Island chain, the wide shallow palm of the highly productive ice-driven Bering Sea, and the delicate and rapidly changing high Arctic systems of the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas. Ecosystem-based management (EBM) offers a holistic approach for managing complex marine ecosystems in the face of increasing pressures. Adequately characterizing the impact of various pressures and drivers, and quantifying the risk to key ecosystem components, habitats, and species is central to EBM and IEAs in Alaska facilitate the critical science and management advice to support the region’s EBM.

Tracking Change

Climate change is a global issue affecting marine ecosystems and species that span multiple international boundaries and is one of the most universal concerns facing fisheries managers around the world. Understanding of the implications of climate change on marine fish and fisheries throughout Alaska is needed to develop sustainable harvest strategies and secure regional food security. The immense and immediate threat to marine species and attendant fisheries posed by climate change is difficult to overstate, and finding climate-literate solutions and management tools mandates international collaboration to develop approaches that can be rapidly implemented across multiple large marine ecosystems (LMEs) worldwide. Keeping pace with a rapidly changing climate also requires fisheries management tools that can accurately and efficiently inform best solutions in an uncertain future, yet implementation of such management lags behind climate-driven changes to species and ecosystems.

Understanding Connections

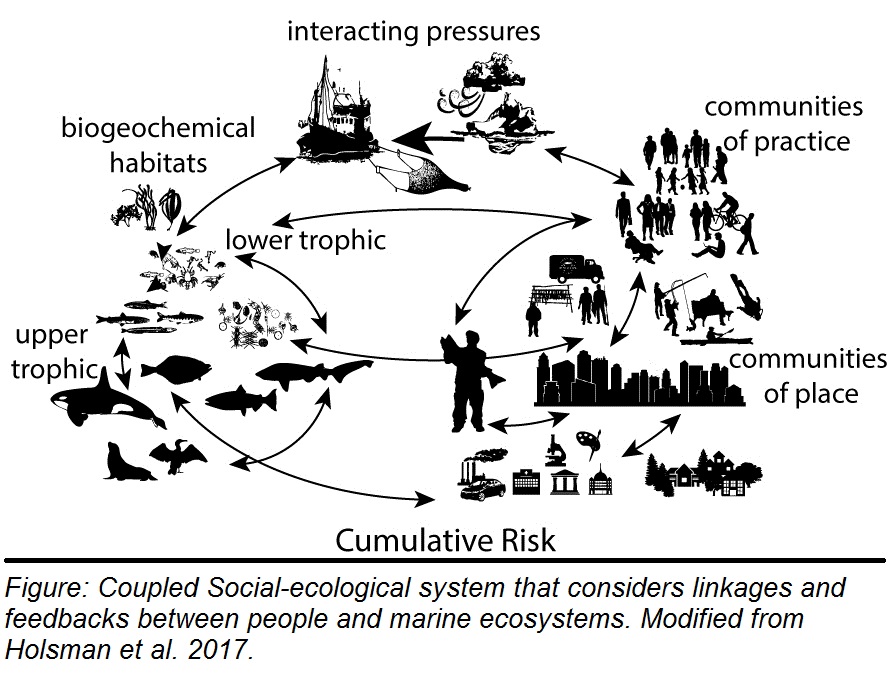

One of the challenges in understanding ecosystem health and risk is the degree of feedback between natural and human systems, which considered jointly, can provide insight into potential management actions and impacts. We use the term “coupled social-ecological” system to describe a system where humans are considered to exert pressure(s) on the natural components of the system and themselves, and to respond (often non-linearly) to pressure(s) from the natural system (or vise versa). In this, a pressure posing risk to an ecological component (e.g., impacts of fossil fuel emissions on calcifying marine organisms) may also represent a benefit accrued to a social component of the system (e.g., manufacturing, energy, or transportation industries). The inverse may also be true: a pressure posing risk to a social component (e.g., a climate shift favoring groundfish fisheries rather than crab fisheries) may represent a benefit accrued by an ecological component (e.g., groundfish). This feedback between and within the natural and social system can be influential and important to consider, yet as Holsman and co-authors describe “while Coupled Natural Human (CNH) system problems are complex, tractable methods for analyzing risk to them need not be.”

IEA methods and models distill this complexity down into manageable changes that can be tracked using ecosystem models and indicators. In doing this we find that natural systems will not simply absorb pressures posed on them by the human system, but rather, are likely to respond, adapt, and exert pressures back on the human system as well as other components of the natural system. Further, because a risk is not distributed equitably among the human or natural components of the system, there is an asymmetry in the benefits and costs between different stakeholders in the community. Capturing such potential responses depends on co-production of knowledge, high-quality ecosystem information, continual evolution of ecosystem models and assessment of risk, and streamlined communication between management and IEA researchers. These elements, therefore, form the foundation Alaska IEAs.

Building Partnerships

The state of Alaska spans a large geographic area which includes 4 Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). The Gulf of Alaska Large Marine Ecosystem is expansive and contains a diversity of cultures, community practices, and historic identities. Engaging stakeholders and building partnerships between resource managers, resource users, and scientists can be challenging.

Our approach is to engage community members through in-person presentations, workshops, and local media outlets. Consistent, regular, and sustained communication and follow-up is necessary for community endorsement, trust, and engagement. Additionally, stakeholder engagement is a required component of Ecosystem-Based Management (EBM) as specified by the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act.

The inclusion of ecosystem science in fishery management decisions is a critical component of effective resource management and NOAA Fisheries has adopted the ecosystem-based approach to coastal stewardship and fisheries science. Building partnerships are of paramount importance in the incorporation of local and traditional ecological knowledge in ecosystem models, which is needed to achieve successful, sustainable, and equitable management of fisheries at local and state-wide scales.

Informing management

Fisheries management in Alaska has a long history of including ecosystem information into management decisions. Over the last 20 years, the North Pacific Fisheries Management Council (NPFMC) has actively engaged in bringing Ecosystem-Based Fisheries Management to the table through the development of annual Ecosystem Assessments, including ecosystem Report Cards, that are presented to the Council alongside quota decisions, the creation of an Aleutian Islands Fisheries Ecosystem Plan, the adoption of an Arctic Fisheries Management Plan with strong emphasis on ecosystem protections, the direct use of stock assessments that include climate drivers and other ecosystem effects, the inclusion of IEA team members on plan teams and other review boards, and through ongoing National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) analyses.

In 2014, the Council adopted a vision statement for management to include “Environmental variability and uncertainty, changes and trends in climate and oceanographic conditions, fluctuations in productivity for managed species and associated ecosystem components, be based on best available science, including local and traditional knowledge, and engage scientists, managers, and the affected public.”

The NPFMC stated their ecosystem-based management goals are:

- Maintain biodiversity consistent with natural evolutionary and ecological processes, including dynamic change and variability

- Maintain and restore habitats essential for fish and their prey

- Maintain system sustainability and sustainable yields for human consumption and non-extractive uses

- Maintain the concept that humans are components of the ecosystem